Never Let a Good Crisis Go to Waste

How changes in public health could change health communication

As I’ve discussed here before, I used to run a lot. In college, our cross country team typically went up to Minnesota for a big meet in that was usually a good marker of how well we stacked up with other Big Ten teams at the midseason mark. One year, we did not run particularly well and it was disappointing. We traveled that far after months of training and hard work just to do not that great.

Afterward, I was standing with some teammates at the wooden board where—back in the olden, pre-electronic-real-time-race-tracking-on-digital-displays that you see at meets now—the officials would staple the paper print-outs of all the results. Seeing that list of who from which team placed where, immediately woke me up.

Okay, I told my teammates, now that we can see this mapped out, we can figure out what to do! We know that next time I can pass these couple Michigan State girls at the end if I hang with them in the middle of the race better. And, you, you can hang a little longer with this Michigan girl and can totally out-kick that other Michigan girl when we are tapering toward the end of the season, and by the Big Ten meet, we can beat Michigan State and Michigan!

We turn around and there’s a gaggle of green and white Michigan State runners who had heard everything I said and were now scowling a little bit at me. I just bounced away and burst out laughing. Time to cool down and try to beat them in a month!

Narrator: The Hoosiers would not beat either team the next month. But, they would be top-15 in two months at the NCAA championship, just edging out Michigan, a huge accomplishment for a team that had finished near last at Big Tens the year before.

This week feels a little similar to me, mentally, to the fall of 2002, (although obviously on a much bigger and more impactful scale that will literally affect lives across the globe). The uncertainty between the November election and now of what could or would happen to public health is being replaced with concrete actions. (Not to mention the impacts of many other executive actions this week, but I’ll be focusing here on public health.)

Many leaders have uttered some version of the phrase, often attributed to Winston Churchill, “never let a good crisis go to waste.” We can and should have our moments of grief, fear, and anger. But, now is the time to strategize and take action. American history is full of people who had to be smarter and faster to fight off threats to their livelihoods. That spirit lives on now but we need to thoughtfully and actively reach for it as it will not necessarily shine through the chaos portrayed on social media.

It will be very hard to put back together all the public health efforts that are being dismantled. I am not trying to be a Pollyanna right now. However, unless you’re currently running a multinational tech corporation, our only option is to look at the results stapled on the board and decide to work together to do something as a team. We can start planning and training for the next few races, and beyond.

As epidemiologist Katelyn Jetelina advises us:

[A]s unsettling as this feels, now is the time to stay steady. Public health world: Do not destabilize. The health of 330 million Americans depends on it.

The added benefit of actively planning and contributing to meaningful efforts to protect and promote public health is that jumping into these activities will feel better than only doomscrolling and doomsharing.

First, the print-outs on the board

Here is a broad overview of the public health-related events that happened this week:

As reported by the Washington Post, the Trump administration told federal health agencies in the Department of Health and Human Services (think NIH, CDC, FDA, etc.) they had to pause all external communication. This includes everything from social media posts and interviews with reporters but also releases of taxpayer-funded data on the bird flu outbreak and meetings of important health advisory committees.

NIH study sections are not currently meeting.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion programs have been ended across the executive branch, and this has hit HHS departments hard. The Trump administration has asked government employees to report any efforts to subtly or subversively work on efforts that involve diversity, equity, and inclusion. This could mean diversifying participant pools in clinical trials so that women are included in research, for instance, is not longer a government-supported effort.

This also affects the health information we can get as members of the public who pay taxes for the creation of this knowledge base. If you now try to go to the National Institute of Mental Health’s webpage for Sexual and Gender Minority Mental Health Research, you get a message that “the page you’re looking for isn’t available” (404’d, as they say).

There are many more in-depth pieces you can read about what has happened this week in public health, but that’s the short version.

What does this mean for health communication?

There are three ways in which the current executive orders are affecting health communication.

1.) The most immediate way is in the lack of government information being communicated to the public. This is information your taxpayer dollars have funded and that can help all of us stay safe. So, hiding it from us violates some of the basic tenets of a government by the people and for the people.

Yet, I understand why not everyone is up in arms about this issues. Most of us go about our daily lives without spending any time reading or viewing messages from federal health agencies, so maybe this does not feel like a big deal. Dear reader, it is, in fact, a big deal.

First, public health officials, healthcare systems, state and local governments depend heavily on these messages and reports for guidance on preventative and mitigation actions that can save lives. This is especially critical for infectious disease surveillance efforts that, as well learned in 2020, can drastically affect us.

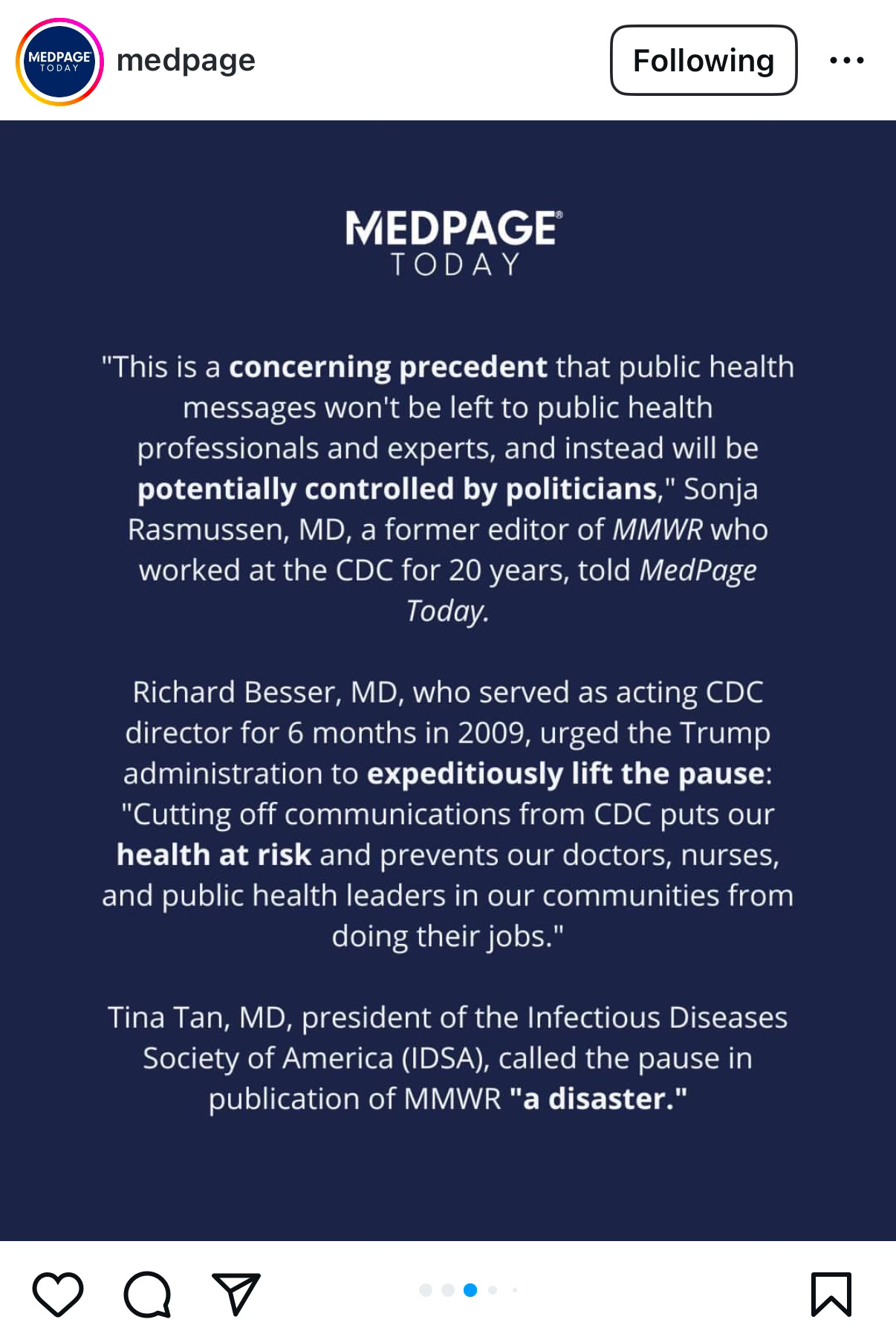

Thomas Frieden, former CDC director, noted one consequence of this action after the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) was not published as scheduled on Thursday for the first time since 1960:

“Every day this vital publication is delayed, doctors, nurses, hospitals, local health departments and first responders are behind the information curve and less prepared to protect the health of all Americans.”

Many other public health officials and physicians have weighed in with serious concerns about how the lack of direct communication between agencies staffed with scientists and the public will foment the continued politicization of health information in America.

Here is a more specific example of the effects of lack of communication:

Bird flu (also called avian flu) is spreading so fast—currently found in every state—that Georgia, the U.S.’s largest chicken exporting state, has had to suspend all poultry activities.

This means the loss of tens of millions of dollars in export revenue, likely lost jobs for people who work in the poultry industry, and record high—wait for it—egg prices.

The CDC and other agencies (likely the USDA) has information about bird flu that could help individuals at higher risk of catching the infection (it can be deadly and has killed people in the U.S.) but that could also help industry and local governments combat the health and economic harm it is causing.

2.) The second primary way these executive actions are affecting health communication is that there will be ripple effects that greatly slow our efforts to improve how medical and behavioral health interventions reach and help those who could benefit from them. While a majority of NIH funding is directed at biomedical research, much of it also funds social science efforts, including health communication research. There are currently many promising medical discoveries that could prevent and treat cancer, slow Alzheimer’s, you name it, but if we do not hear about it or do not know the best way to talk to the public about it, then those medical accomplishments will not benefit all of the taxpayers that funded that research.

The pausing of NIH study sections also means that people in every U.S. state and territory are likely to lose out on billions—with a b—in economic boosts brought about by the jobs, healthcare savings, and improved productivity brought about by a healthy society. A coalition of research institutions called United for Medical Research analyzed NIH spending in 2023 and found the following:

In Fiscal Year 2023, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) awarded $37.81 billion in extramural research funding to researchers in all 50 states and the District of Columbia… this funding directly and indirectly supported 412,041 jobs and produced $92.89 billion in new economic activity nationwide — or $2.46 of economic activity for every $1 of research funding.

3.) I would argue this third way is more indirect but still important. These executive orders are affecting health communication because they are news hooks that generate media coverage and public discussion about public health. Anecdotally, not many people were talking about public health and healthcare in my feeds last Thursday, but boy were they talking about it yesterday.

In a media-saturated world where it is hard to get people’s attention focused on health, there are some benefits to this. But, as most of us well know by now, it can foment the rapid spread of health and policy misinformation, too. Time—and our own actions—will tell how this uptick in attention to federal public health policy plays out.

Now, the planning and training for upcoming races

That’s a synopsis of what is happening and how it is shaping health communication. What can we do about it, if anything? I have some suggestions.

Make a smart training plan

Just like runners have to make a training plan that helps them get faster without training so hard as to get a stress fracture or hamstring pull, so, too, do citizens of a democracy need to figure out how to get enough of the right kind of health information to inform effective action plans without becoming overwhelmed or burned out.

If you feel overwhelmed or sad scrolling through social media or watching cable news, then cut back on those activities. Rely on trusted thought leaders to filter out the most important issues of the day for you. You can trust your gut about the thought leaders or writers who make you feel smarter and grounded and spend 30 minutes one day curating your social media feeds and email newsletter subscriptions so you are more focused on them.

Then, try to stay consistent in keeping up to date on those issues that affect you and your community and being armed with reliable knowledge will help you to better speak up when the opportunity comes.

How often to race?

Races take a lot out of a runner. You need to plan the timing and location of your races carefully. As for timing, sometimes racing consistently on a smaller, less pressure-filled stage, helps people get more comfortable and sharp in their execution. For others, racing is draining that it is better to train a lot and only show up to the big meets when it’s time to shine.

Know your personality and how introverted or extroverted you are to decide how and when to speak up. The story of the Episcopal bishop of Washington, Right Rev. Mariann Budde, addressing Trump about the topic of mercy during his post-inauguration prayer service is a great example of where even a quiet, calm voice at the right time and the right place can make a big wave.

Where to race?

We cannot be all things to all people. And it could help if, in our efforts to support public health and improve the physical and mental wellbeing of fellow humans, we did not flood the zone with any additional chaos. But, if you care about health, then post every once in a while and talk to people every once in a while about health issues. Doing it in a calm, matter-of-fact way, can help build trust and report. If you area is education, focus educating yourself about how those policies are affected and talking regularly about that. Maybe your area is physical activity, be it by profession or hobby. Great, find what you can about that. And stay consistent in telling good stories, alerting people to potential areas of concern, and staying connected. This can help us all to both make a difference without burning out or suffering from overwhelm.

Race strategy is crucial

Go out too fast and someone will sprint past you at the end. Go out to slow, someone will make a big gap that you can’t overcome. In short, once you are ready to talk about health, think through how you want to do it. How will you frame your messages and what will you tone be?

Understanding how people come to see health information, how they process it, and how they respond to it can make you a better health communicator. So, don’t always post or talk to other people based on how you feel or what works for you. Instead, know your audience and know how humans, generally, react to health information.

Base your messaging approach on what communication science tells us are more effective ways to talk about health. That is the kind of information I try to dispense in this newsletter and a full review of every persuasive health communication strategy is beyond the purview of this single post (or a career of work in this area, even). However, here are a few key points for this particular moment in time:

We are cognitive misers: We can only process so much information so closely. So, know that if you share a news article on Facebook, many of your friends may see the headline, but very few are going to click on the article and read any of it. If you want to make a point, on person or online, get to the point fast.

We can only be intensely negative for a short amount of time. Although our brains are primed to quickly attune to scary or angering information, we can’t sustain attention to it for long. If you share every bad, scary thing you see happening in the world, people will start to get desensitized and may even, intentionally or unintentionally, avoid you or your messages because we were not built to spend the majority of our days feeling bad. We need positive emotions to get us out of bed and motivate us to pursue longterm goals. Rebuilding public health is definitely a longterm goal.

Even if the news is scary or bad, at this point, think about just giving some facts neutrally. You don’t have to be overly cheery about it. But, this does get to another research-informed suggestion…

Start with positive before getting to the harder truth. The mood-as-resource framework argues that positive emotions can serve as a type of mental resource, or buffer, that makes it easier for us to want to listen to tough information. Post cute pet videos and memes or start with a joke before delving into the more pressing matters of healthcare policy. If talking to someone in person, ask them to talk to you about a passion project or something they enjoy or are proud of and if the conversation does turn to current events, then they will have more bandwidth to talk about it.

Relevant specifics are better than vague generalities. Amounts of money I see in the news now all sound like Monopoly money to me. What does it mean that Elon Musk is worth $427 billion? [Insert Austin Powers meme about a million dollars here.] So, if the opportunity presents itself, where there is a national news story about $XX billion being cut from this public health effort, see if you can find local numbers.

A good example is yesterday’s news about the NIH. The United for Medical Research consortium started sharing its interactive map that can show people how much the NIH benefits the economy in each state. So, if that “$92.89 billion in new economic activity nationwide” number I listed above seems hard to grasp, maybe it will help to know what the annual economic effects of freezing NIH activity in Pennsylvania would be, for instance. I saw a lot of friends doing this online yesterday, which was great. The NIH website, for the moment at least, even allows you to look up funding by congressional district.

Stories and people are sometimes better than statistics. Exemplification theory and research on compassion fatigue teach us that we are typically more attuned to the stories of individuals who have a name and face that we can see and connect with on an emotional level. If you have some example in your life, a niece with a rare disease who benefited from a drug supported by NIH clinical trials, tell that story. Even better if you can use specifics about how the research was funded and which specific drug helped. Many people do not realize how much of the health and medical care we rely on today is the result of federally-funded research, and part of the reason why is we do not talk about it a lot.

Call—on the phone—your senators and representative. This is a form of health communication, too. Tell them how freezing NIH research hurts you and your neighbors and the economy. They are skeptical of bots flooding their email, but policy makers pay attention to phone messages. If you do not want to talk to a staffer in real time (fellow elder millennial, raise your hands), call at night and leave a message. This is important for state and local officials, too, who may be in less gerrymandered districts and more sensitive to constituent outreach. A lot of the flood of executive orders is hoping to overwhelm the average person as we deal with so many other things on a daily basis. Take 60 seconds a day to let them know you are still paying attention and you still care. It can add up.

Often, the training—the process—is as or more important as the race result

Even if these difficult changes in public health communication are not reversed on February 1, that will not mean the race is over. There is always another race, another event for which we can prepare. And, the process of trying to be thoughtful and connect with other people will pay off on a personal and societal level. Author and founder of the organization Run for Something, Amanda Litman, put it well in a social media post last week and I have been holding onto her words every since:

Barely three days into Trump 2.0 and one thing is clear: Wherever & whenever possible - state & local govt, corporations, nonprofits, PTAs, soccer leagues, whatever - leaders will need to be *even more* compassionate, inclusive, authentic, & genuine.People are going to be starved for it.

Volunteer for a local community medicine clinic. Coach little league, bring a casserole to the family with lots of little kids suffering through winter cold and flu season, walk a neighbor’s dog for them. There are many ways to reconnect, and they are all important, no matter how small. Not only will we fill better and our neighbors will feel better, but when the midterm elections role around, there will be a halo effect of your effort and empathy that may draw more people than you realize to follow you to the polls.

Never let a good crisis go to waste. No doubt, this is a crisis, for people who care about public health, for people who want to contain infectious disease spreads, for cancer patients who cannot get cutting edge treatment, for all of us as top health researchers consider leaving the United States for greener pastures. However, it can jolt us awake, too, in a way we may need post-pandemic to reconnect and reengage.

That’s all for today. Thank you for reading and please send me your suggestions for future Healthy Media posts.

P.S. Here is Pancake the pug supporting these writing efforts from her perch in the playroom/office behind my computer.